The rivalry between Puerto Ricans and Dominicans goes back decades. Neighboring islands, and their diasporas in the United States, compete on everything. The question of who is better in baseball is settled almost every year with a new headline matchup. Doc won an exhibition game in New York on November 15, but was defeated by Puerto Rico in the 2023 World Baseball Classic. In the kitchen, the conflict is between Puerto Rico’s mofongo and the Dominican Republic’s mangi, two gilly plantain staples. And in music, there are arguments about who has more rhythm on the dance floor and who makes more hits. An outsider has thrown this comical, albeit pointedly, at each other on the Internet and thinks these two are really enemies, but the opening of Bad Bunny’s Debí Terror Mess Photos World Tour in Santo Domingo revealed what we’ve always known: it’s all playful love-interior familia.

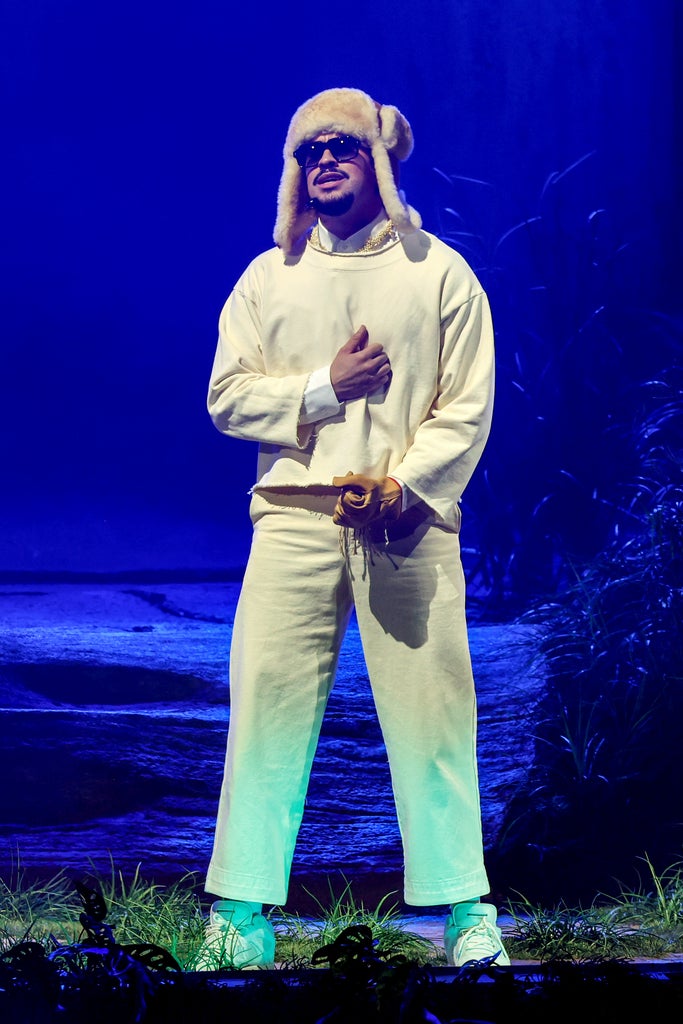

On November 21, the Puerto Rican three-time Grammy winner, born Benito Antonio Martinez Ocasio, kicked off his highly anticipated Stadium World Tour with two sold-out shows in the capital of the Dominican Republic. One night, Bad Bunny, named the top Latin artist of the 21st century, welcomed a crowd of about 50,000 people to the Estadio Olimpico Felix Sanchez, “I really enjoy being a tourist here, although I don’t know if ‘tourist’ is the right word, because when I’m here, I feel at home.” And everything about the show celebrated the shared heritage and close ties that the two islands have built together.

In the audience, Dominican women completed their concert outfits with Puerto Rican pava hats — or, as La Zona colonial street vendors renamed them, “el sombrero de bade bani.” Meanwhile, Puerto Rican fans who missed Bad Bunny’s historic 31-show residency in San Juan’s El Choli made the short trip to Santo Domingo, snapping photos in front of wall-length Dominican flags.

The tour’s global presentation sponsor, Hilary Hansi, created experiences that seamlessly blended the two cultures outside the stadium and in downtown Santo Domingo. In a Hennessy-branded casita by the show, Boris, like model John Smalls y Doms, and actress Dasa Polanco Domino, sat down to play Two Flags at Home, while Alex Sensation spun on ’70s salsa and meringue tipico. Fans refreshed from the Caribbean humidity with the Hennessy de Coco, a spin on the Pietro de Coco that combines coconut, tropical fruit, and Hennessy, and the Hennessy Passion, a mix of passion fruit, lemonade, and Hennessy — two cocktails that will be available throughout the tour. Among the activities, there was a Paraguayan stand offering cognac-infused versions of the shaved ice treat popular on the cobblestone streets of Viejo San Juan and the classic Dominican chamis.

The combination made sense because most of us, with roots in Borkan or Cassia, have known them our whole lives.

Although our shared history can be traced back to the Taino, the indigenous peoples who once inhabited the islands of the Greater Antilles, and the Spanish conquest that brought violent genocide and African slavery, is the solidarity that emerged from this common struggle. For generations, Puerto Ricans and Dominicans have stood together, supporting and fighting alongside each other in postcolonial and social justice movements.

To begin with, the Dominican Republic’s fight for independence, first in 1821 and again in 1844, served as a symbolic and inspirational model for Puerto Rican nationalists. During their bid for independence in the nineteenth century, Puerto Rican revolutionaries often took refuge in Santo Domingo, where they could safely network with nationalists across the Caribbean, and publish colonial materials. In 1868, when Puerto Ricans revolted against Spanish rule for the first time during El Grato de Llores, they planted a revolutionary flag featuring a white cross dividing the flag into four rectangles, a tribute to the Dominican flag and a tribute to the trans-Caribbean revolutionary network.

Decades later, now as a US colony, the people of Puerto Rico are using what political power they have to push back against the federal government’s anti-immigrant policies in Puerto Rico, which have primarily targeted Dominican immigrants. Borykwas regularly protest street raids, deportations and anti-immigrant legislation. Organize food, clothing and medical brigades to help Dominican families economically affected by the immigration crackdown. And even shelter Dominican immigrants in churches and community halls that have become safe havens.

“Everything about the show celebrated the shared heritage and close ties that the two islands have built together.”

Raquel Richard

A similar solidarity exists within the diaspora. In New York, where lively animosity between Puerto Ricans and Dominicans began in the 1970s — when Dominicans moved in large numbers to historically Boricua neighborhoods such as the South Bronx, Washington Heights, and the Lower East Side — new forms of solidarity have emerged. The Young Lords, a Puerto Rican revolutionary group born in Chicago that later spread to New York, included many Dominican women and men, who fought together for housing rights, access to education, and community health programs that affected both communities. At the same time, East Harlem’s El Museo del Barrio served as one of the few centers where Puerto Rican and Dominican youth collaborated on arts, education, and cultural projects.

Living side by side in housing projects across the city, the two groups did what they, arguably, did better than anyone else: crack jokes. As my Puerto Rican father, who grew up in New York in the 70s, tells me, no one was safe and everything was ready to be teased: the accent, who played smart with the girls, and who had the best rum. Over the years, these neighborhood jerks have played out, with Puerto Rican men now laughing that their Dominican friends wear their pants and Dominicans teasing their Puerto Rican brothers for dressing like they’re in an early 2000s Paddy Creek music video.

A comedy skit called “Puerto Ricans vs. Dominicans,” published by Flama in 2015, captures the playful beef perfectly. In the five-minute clip, the two men go back and forth, hilariously arguing about which culture has better style, music and food, only to have a mother in Rolos reveal that the two are actually brothers, each Puerto Rican and Dominican.

And this is the second fact: in the diaspora, Puerto Rican and Dominican communities often intermingle, forming families that keep us even closer. If you don’t have a Dominican tio, are you even Puerto Rican? Are you even Dominican if you don’t have a lover who is half-sack and some other distant relatives who have lived in Puerto Rico for decades? We are, quite literally, family. During Bad Bunny’s second show in Santo Domingo this weekend, he brought out Romeo Santos, who is both Dominican and Puerto Rican, to perform a bachata version of “Bouquet.” And many of our favorite stars in music, film, TV and social media share the same mix. Our identity hangs together like the woven fibers of tono baskets, a shared ancestral practice I just learned about during my recent visit to Centro Cultural Tono Casa del Cordon in Santo Domingo.

A guy I used to date, who just happened to be Dominican, always told me, “Where there’s a Puerto Rican, there’s a Dominican nearby.” And he wasn’t wrong. From New York and New Jersey to Worcester, Allentown and Orlando, there are completely mixed neighborhoods. We unite because we know that, despite all the jokes and competition, we see and understand each other. Our food and music are made with the same ingredients. Our accents and slang may differ, but we understand each other’s dialect more easily than anyone else. We feel safe together. We feel at home. And like siblings who fight but will throw their hands at anyone who really stands up for their family, we tease each other relentlessly, and hilariously, con amor y respeto.

“We are two cultures, two countries, and two islands that have fought generations of conquest, injustice, and marginalization in the Caribbean and states – y todavia estamos aqua, juntos, teasing each other, y bien kabern.”

Raquel Richard

And that’s why, when I threw my hands in the air and jumped for joy at Dr. K’s Bad Bunny’s show this weekend, yelling, “Puerto Rico,” mi territa, “Estebien Cabran,” tens of thousands of Dominicans around me were jumping and yelling it, and it meant it.

That’s why I teared up when Benito announced this performance, “La República Dominicana Est Cabernet Tambien.” Because we are two cultures, two countries and two islands that have fought generations of conquest, injustice, and marginalization in the Caribbean and states – y todavia estamos aqua, juntos, teasing each other, y bien kabern.

What are you looking at? About some more R29 goodness, here, here?